The Factual History of George E. Merrick and The University of Miami

By, June Thomson Morris: Author, Greetings from Paradise, a stage play written in honor of Coral Gables’ 100th Anniversary

In this centennial year of the City of Coral Gables, notable local publications have produced special editions listing prominent points of pride for the city, one of them being the foundation of the University of Miami. I first learned of the revision to the university’s history when I received in the mail a Community Newspapers Centennial Edition. I called the paper’s publisher, Grant Miller, to ask why he had omitted George Merrick’s name in the story of the university’s founding. He told me that he had simply “cut and pasted” the paragraph from the City of Coral Gables’ own Centennial website. After verifying that the revisionist history was on the city’s own special website, I got in touch with the city’s Director of Communications and Public A airs, Martha Pantin, who told me she got the information from the University of Miami’s website. Her sta had done the same ‘cut and paste’ that Community Newspapers had done.

This experience is a great example of the perils of digital communications in an era of ‘cut and paste.’ Revisions to facts can be made and then repeated endlessly by the touch of f ingers on the keypad until those revisions themselves become the facts. It’s a muddling of history that obviously has serious ramifications globally, nationally, and locally for institutions as well as for individuals, both dead and alive.

In the case of George Merrick, I feel the need to clear up misconceptions. This man, who died 83 years ago, is not here to defend himself. When the Board of Trustees voted in 2020 to remove Merrick’s historical association with the university, they did so based on a student-led petition that listed “several supporting documents and sources” to legitimize its claim that Merrick, “…both held and acted upon racist, segregationist beliefs throughout his life; including in his role as head of the Miami-Dade Planning Board.”

The First “Supporting Source”

It is interesting that the first source listed in the petition takes one to a UM library page in which discriminatory and segregationist practices by the university itself are detailed from the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s. George Merrick died in 1942. There is no record of him ever saying or writing anything about whether Black students should or should not be allowed to enroll at UM. He donated land and money to establish the campus. He did not set the ground rules. So why did the university itself continue to discriminate against Black students and make them feel unwelcome when they were eventually enrolled alongside white students?

Here is a quote from the UM library page: “President Stanford was sympathetic to the students’ agenda and met repeatedly with UBS (United Black Students) leaders. He had to mitigate their fervor with the slow pace of university administration…” That happened in the late 1960’s, more than 20 years after Merrick died. Should names of former presidents of UM be removed from campus buildings and streets?

scholar.library.miami.edu/umdesegregation/60s.php.htm

Today, the university’s demographics show that Black students make up just 9% of the student body and just 7% of the faculty/sta . There has never been a Black president of UM nor a Black Chairman of the Board of Trustees, which has historically been majority white. What role did Merrick play in these current numbers? The statistics alone show a gross hypocrisy on the part of the university in tarnishing Merrick’s historic legacy.

The Second “Supporting Source”

The second supporting source listed in the petition is an online article by WLRN published in 2018. The article describes an incident where a 12-year-old Black girl was called a racial and homophobic slur by another child during a one-week STEM summer camp at UM. The camp took place in UM’s Merrick Building. WLRN’s unnamed reporter writes: “In the 1930’s, [Merrick] advocated for all black families to be pushed out of Miami’s city limits and into “negro towns” in West Miami-Dade.” The article then quotes the girl’s mother, who said in light of that information, she feels the building is “unsafe.”

The Third “Supporting Source”

The third supporting source is a piece from The Florida Historical Quarterly on “Race, Housing, and Government Policy in Twentieth-Century Dade County” published June 19, 2020. While the link in the petition does not lead to the article, I located the source, which provides good background information on discriminatory practices in Florida history, and has nothing to do with George Merrick.

The Fourth “Supporting Source”

Finally, the petition references a speech Merrick gave to the Miami Realty Board in May of 1937. Oddly, the petition does not quote from the speech directly. Instead, it quotes historian Reymond Mohl in summarizing Merrick’s remarks: “In a speech to the Miami Realty Board in May of 1937, Merrick proposed a ‘complete slum clearance…e ectively removing every negro family from the present city limits.’ This black removal, Merrick asserted, was ‘most essential and fundamental’ for the achievement of Miami’s ambitious planning goals.”

SUMMARY BREAKDOWN

Both quotes used in the petition – and the only ones referencing Merrick – are secondhand paraphrasing by an unidentified reporter and an author. This is not factual information, but hearsay, and possibly slanted to promote an agenda. There are no direct quotes from Merrick himself. Yet, based on these citations, the University’s Board of Trustees voted to remove Merrick’s name from a parking garage and eliminate any mention of his contributions from the university’s public narrative.

So, let’s talk about this…from the beginning: THE FACTS

In the beginning: A time Capsule

In 1925, George Merrick donated 160 acres of land and $5 million toward a $15 million endowment to establish the University of Miami. In today’s dollars, that is an endowment of $18,362,000 million from Merrick, plus the 160 acres of land at today’s value of $14.32 million per acre, is today worth $2.294 Billion. Shouldn’t we be grateful for such a gift that is responsible for the university’s very existence?

From the 1890’s – 1940’s, the U.S. was in the Jim Crow Era – a period defined by segregation, exclusion, and discriminatory local ordinances. While outright racial zoning was struck down in 1917, restrictive covenants in property deeds remained legal, barring Black families from living in white neighborhoods. These policies were institutional, widespread, and devastating.

The Legacy of Dana A. Dorsey

Dana A. Dorsey, a first-generation free man with a fourth-grade education, became one of Florida’s first Black millionaires through real estate. He created Colored Town (now Overtown) to provide housing for Black workers barred from white neighborhoods. Dorsey also built schools, parks, a hotel, and a bank for the Black community, and once purchased land next to Miami Beach to create a “Negro resort.” That land was sold to Carl Fisher’s company and is today Fisher Island – among the most exclusive residential areas in the world.

Was Dorsey a segregationist for creating a Black community? Of course not. He was working within the constraints of his time to provide safe and prosperous opportunities for Black families. His story underscores the importance of historical context.

The Legacy of Carl G. Fisher

Carl Fisher, like Merrick, employed many Black laborers in building Miami Beach. He, too, recognized the need for better living conditions for these workers and wrote at least one letter proposing a town and beach for them on Miami Beach, but those plans never materialized. Though his deeds did not explicitly restrict Black ownership, Black families still could not buy property there. Additionally, only the wealthiest Jewish families were allowed to buy homes and property on his portion the Beach. Should we demand that Fisher Island be renamed?

The Legacy of Henry S. Flagler

Henry Flagler housed Black and white railroad workers in tent cities and crude wooden barracks. During the 1906 hurricane, over 200 workers were literally swept to their deaths. There is no record of Flagler ever attempting to improve their living conditions. Should we demand that Flagler Street be renamed?

The Legacy of George E. Merrick

Merrick transformed his family’s farm into one of America’s first planned cities. Coral Gables was incorporated in 1925, devastated by a hurricane in 1926, and financially crippled by the Great Depression. Merrick was removed from the City Commission in 1927 and accused of financial mismanagement. By the time of his 1937 speech to the Miami Realty Board, Merrick was a private citizen and had no jurisdiction over Coral Gables, nor any other municipality.

His address, entitled, “Planning the GREATER MIAMI for tomorrow,” was 24 pages in length, and covered many urban development issues. The issue of Black housing was contained on pages 12-14. In these pages, Merrick was able to express his concern for the well-being of Black residents:

Here are a few direct quotes from his speech:

“Today one-third of our present population is negro… This third of our present citizenry are e ectively denied water access and ‘water use.’ Now collectively, as well as individually, we cannot receive fairness, unless we give fairness.”

“It is proposed…that a great Bay beach be established and forever preserved for negro use…” (At a time when Blacks were not allowed on any beach)

“Next, it is visioned.. a complete slum clearance… not in the ‘Marble City’ or Liberty City manner… but modeled after Grants Town in Nassau. Here… each plot is a quarter to an acre… covered with tropical fruit trees…houses are what these people want.”

Merrick was not advocating for forced removal or ghettoization. He proposed a forwardlooking solution rooted in dignity, health, and self-su iciency. These ideas aligned with the era’s urban planning principals, which meant that they could be achieved and not just given lip service.

To understand the situation better in historical context, it helps to use pictures:

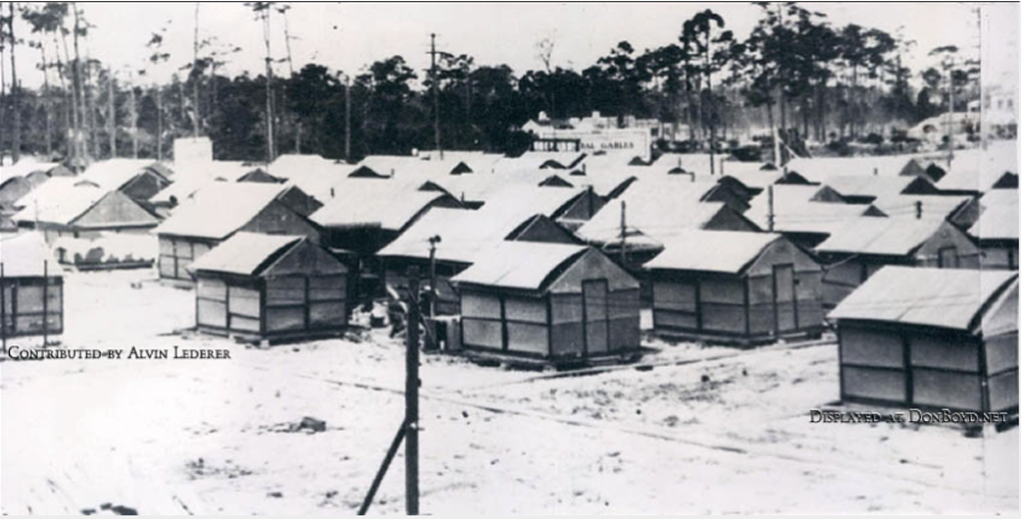

Here is a typical house in Coral Gables. George Merrick was not advocating the forced removal of Black families from houses like this. He was not suggesting that ownership of homes be wrestled from Black citizens and that they instead be sequestered in ghettos outside of cities. To the contrary, he called for the removal of ghettos then in existence in South Florida. Ghettos like this one:

In 1933, the Federal Government passed the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC), a New Deal invention to try and ease distressed mortgages and prevent Depression foreclosures. However, it also implemented a now-infamous appraisal system that created color-based “Residential Security” maps for over 200 cities, grading neighborhoods by perceived lending risk. Predominantly Black or integrated neighborhoods were invariably marked in red (“hazardous”) indicating high risk, a practice that denied those areas access to a ordable home loans. These confidential HOLC redlining maps institutionalized existing private biases and set the template for decades of disinvestment. The term “redlining” originates from HOLC’s red-shaded maps, which banks and insurers later adopted to refuse loans in Black communities. This federal appraisal policy buttressed urban segregation and hindered Black ownership, as Black families found it nearly impossible to get mortgages in redlined zones.

And who was responsible for this Progressive Mandate that hurt Black families for decades? Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Should we ask that his name now be removed from any monument, building, park, or school?

Merrick bought 19.61 acres from Flora MacFarlane, the area’s first female homesteader, and built a neighborhood that was eventually annexed into Coral Gables, expressly for his Bahamian and African Bahamian workers.

Here is a picture of one of those houses that Merrick built, of which there were 32 originally. Many of the houses are still owned by the original families who settled in the area in the late 1800’s. The houses provided sanitary conditions with a clean water supply on large lots.

“Merrick credited the Bahamians for their influence, inspiration and other valuable knowledge in working with local natural resources such as coral rock, and other tropical materials. Merrick also recognized the contributions of the Bahamian workers and artisans in helping him develop Coral Gables. Many years later, Merrick would honor these black Bahamians in a series of stories he entitled, “Men of the Magical Isles.”

– Karelia Martinez Carbonell, President of the Historic Association of Coral Gables.

Where We Stand Today

Coral Gables, 100 years later, is a very expensive city to live in and only 4% of residents are Non-Hispanic Black. We have far to go in achieving equity – but laying that burden on one man who died in 1942 is both inaccurate and unjust.

I have read everything I could find about Merrick, and about Coral Gables and Miami Beach, for the play I wrote in honor of the city’s Centennial called, Greetings from Paradise.

My conclusion:

1. Merrick was not a racist OR a “monster” as I have heard it quoted from someone at UM who holds George Merrick in low esteem. He was not “two people” – one who did great things and one who was a segregationist and a racist. He was one person: A man of a di erent time who cared about all people. His parents were abolitionists.

2. When he built Coral Gables in 1924-1926, the entire country abided by segregationist rules. Merrick did not write those rules nor was he a social crusader. He was a farmer turned developer inspired by the city beautiful movement. His great hope was that everyone could live in peace and harmony, and aspired that in creating a beautiful city, he would encourage it. He was a poet at heart and a dreamer. His writings are of a kind, sensitive man.

3. Merrick is the only early developer of South Florida who bought land and created a Black neighborhood with houses that are still owned by the original families. He provided sanitary conditions for his workers and their families with running water and areas for children to play and plant fruit trees. He cared very much for the health and safety of his workers and for the entire Black community of South Florida. His speech to the Miami Realty Board proves it.

4. In 1937, he had no political power but still used his voice to advocate for improved Black housing.

Merrick could have remained silent. Instead, he spoke out – and for that – the university canceled him. It is time to restore his name, his legacy, and the historical truth.